Let’s rejoin our story in the session we did with Emma Barker, who led us through a discussion of Fried’s intervention into eighteenth

century French painting. Barker stressed that an abiding methodological lesson

has been introduced into studies of the period through Fried’s insistence on

taking historical art criticism seriously—in reading it holistically, treating

it as an object to be explained, not simply cherry-picking for choice quotes that

illustrate points in an anecdotal way. In this mood, Fried critiques historians

who have dismissed the significance of the re-assertion of the hierarchy of

genres and the central importance of history painting as operating under

anachronistic prejudice (TSF, 545). He argues instead that these concerns were

central to a historical revolt against the Rococo ca. 1750, led by philosophe Denis Diderot. (TSF, 551)

What is crucial for Diderot in Fried’s reading is the concentration of energy

and expression not only by a new-found insistence on unity within painting (TSF

559), but a commensurate demand for constraint within a single temporal instant

of the narrative depicted. As he puts it: “The new emphasis on unity and

instantaneousness was by its very nature an emphasis on the tableau, the

portable and self-sufficient picture that could be taken in all at once as

opposed to the ‘environmental,’ architecture-dependent, often episodic

decorative project [favored by the Rococo] that could not.” (TSF 566) In this

sense, the developments he traces in the essays that would culminate in Absorption and Theatricality (1980) are

understood as anti-Rococo and particular to France. (A&T, 1-2)

This concentration on the tableau format also moved with a

new kind of self-consciousness about the painter’s enterprise—a withering

intolerance for signs of the painter’s meretricious catering to the beholder

for whom the picture was made. So, at once, “a painting had to call to someone,

bring him to a halt in front of itself, and hold him there as if spell bound and

unable to move.” (TSF 570) Yet, to do so successfully, the painter had to

accomplish “the supreme fiction that the beholder did not exist, that he was

not really there, standing before the canvas.” (TSF, 581) Fried’s name for the

privileged means of achieving Diderot’s mandate is, of course, “absorption,”

which he defines as “the state or condition of rapt attention, of being

completely occupied or engrossed or (as I prefer to say) absorbed in what he or

she is doing, hearing, thinking, feeling.” (AMTFP, 143) Chardin is an important

figure in Fried’s account of this absorptive aesthetic—which turns out to

extend back to seventeenth century figures including Caravaggio, Poussin,

Vermeer and Rembrandt (AMTFP, 165)—insofar as he was able to fulfill Diderot’s

brief, as it were, naively. He depicts everyday scenes in which figures appeared

so absorbed in their activities that they turn away from or simply ignore the

beholder. “In Chardin’s canvases the persuasive representation of absorption

appears to have been achieved, to have come about naturally, almost

automatically, in and through the objective representation of ordinary

absorptive states and activities.” (AMTFP, 172-3) Relations between this kind

of aesthetic and the drive for “presentness” are certainly there for the

taking. In Chardin:

The very stability and

unchangingness of the painted image are perceived by the beholder not as

material properties that could not be otherwise but as manifestations of an

absorptive state—the image’s absorption in itself, so to speak that only

happens to subsist. … [We see] a single moment … isolated in all its plenitude

and density from an absorptive continuum the full extent of which the painting

masterfully evokes. Images such as these are not of time wasted but of time filled (as a glass may be filled not

just to the level of the rim but slightly above). (A&T, 50-1)

Pictures like these, Fried continues, visualize “an

unofficial morality according to which absorption emerges as good in and of

itself, without regard to its occasion; or perhaps it is simply that Chardin

found in the absorption of his figures both a natural correlative for his own

engrossment in the act of painting and a proleptic mirroring of what he trusted

would be the absorption of the beholder before the finished work.” (A&T,

51)

Natural and automatic as his efforts appear to Fried,

Chardin is also a transitional figure. In this way, it is Greuze—Chardin’s

inferior successor, as typically judged by modern standards—who is actually

more important to Fried’s story. For, where Chardin can simply, naively

overcome the primordial theatricality of all painting simply by posing his

depicted figures as turned away from or otherwise ignoring the beholder, Greuze

has to achieve those effects and does so by initiating a program of visual

drama. Only by contriving events of such heightened emotional and sentimental

drama can Greuze achieve the unity demanded by Diderot whereby all figures will

remain locked into the concerns proper to the painted world that they won’t be

drawn out by the tractor beam of the beholder looking at them. From Greuze

onward, “the dramatic representation of action and passion, and the causal and

instantaneous mode of unity that came with it, provided the best available

medium for establishing that fiction in the painting itself.” (TSF, 581) Although

Fried is consistently hostile to the construal of modernism as reduction (see

HMW, 221-2), he does cast the shift from Chardin to Greuze ca. 1750 this way:

“The everyday as such was in an important sense lost to pictorial

representation around that time. The latter was a momentous event, one of the

first in the series of losses that together constitute the ontological basis of

modern art.” (AMTFP, 174)

Now, a program of contriving pictorial unity and drama

sufficiently powerful that it will stop a beholder dead in her tracks, but that

has the effect of ignoring the beholder that the picture is designed to attract

all traffics in what Fried variously calls “paradox.” (See TSF, 581; AMTFP, 174)

In his critical writing on Diderot, literary theorist Jay Caplan usefully draws

out the centrality of paradox to the philosophe’s

thought and his preference for the literary form of the dialogue. (FN, 4) “Only

in dialogue—in the shifting movements of conversation and dialogic

confrontation,” as Caplan puts it, “could he find a sense of his own identity,

as well as approach the fleeting object of his thought.” (FN, 7) One of the

paradoxical operations that Caplan sees in Diderot’s thought turns around the

structure of the tableau (considered here as a literary device, informed by the

experience of eighteenth century painting), which so impresses a reader that

she is compelled to recount the scene repetitively. In this sense, the reader

“plays what is literally a part, a fragment; he aims to replace a part that the

tableau has lost … as if by accumulating partial images, one could suggest that

the tableau is and always has been whole.” (FN, 17-18) A fragment that stands

in place of the recognition of difference, the tableau is thus construed as a

fetish “in which the transitoriness of the real world is magically transformed

into an ideal fixity.” (FN, 18) A reading like this has clear implication for

Fried’s account of Chardin’s filled instances noted above.

Caplan, however, also introduces a second framework for

understanding the tableau and its screening of difference. Noting the ways in

which Diderot’s literary tableaux frequently take their poignancy from

highlighting the loss of a family member, Caplan turns to a language of

sacrifice to explain the dialectical chain-reaction these passages provoke:

These tableaux express a desire for

reconciliation, a desire to make up for what the family has lost. However, that

loss or absence is always implicitly replaced by a silent beholder who

identifies with the suffering of the virtuous family members and must

vicariously fill in for those who have departed. In this manner, what has been

sacrificed in a now-fragmented family—the missing part—reappears outside the tableau in the figure of the

beholder. When he sees the tableau … the beholder makes a sacrifice equivalent

to the original one, to the ‘making sacred’ of a family member. (FN, 22)

So, as the reader/beholder of the tableau sacrifices himself

with his own sympathetic sense of loss even as he thereby reconciles the

wholeness of the represented situation, Caplan identifies a structural

difference between Diderot’s literary works and the paintings analyzed by

Fried. He puts it this way: “The

tableau is always minus one. Diderot’s written tableaux are therefore

structured differently from the contemporary paintings that Michael Fried has

so brilliantly analyzed. In the written tableau, a loss inside the tableau

constitutes the beholder outside it.” (FN, 23)

Although I am not entirely convinced by Caplan’s reading, I

think the introduction of sacrifice is highly productive for understanding the

emotional drama of Greuze and for apprehending the broader stakes of Fried’s

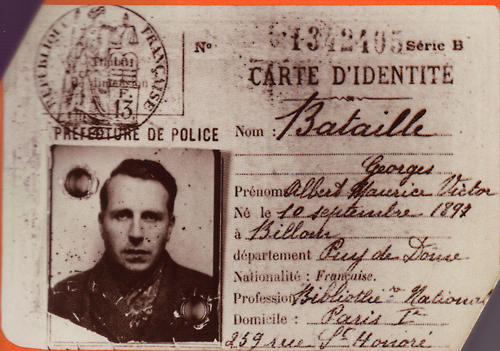

writings on eighteenth century French painting. In class, we used a catalyst

from Georges Bataille, an excerpt from his short essay called “Sacrifice, the Festival and the

Principles of the Sacred World.”[1]

What is crucial to Bataille’s account of sacrifice is that the ritual violently

pulls entities from the profane, utilitarian economies of production in an

excessive act that releases them into sacred immanence. Sacrifice, then, is a

lacerating rupture of individuation that restores the sacred order of community

and its connections with the holy:

To sacrifice is not to kill but to

relinquish and to give. ... What is important is to pass from a lasting order,

in which all consumption of resources is subordinated to the need for duration,

to the violence of an unconditional consumption; what is important is to leave

a world of real things, whose reality derives from a long-term operation and

never resides in the moment—a world that creates and preserves (that creates

for the benefit of a lasting reality). [...] Sacrifice is made of objects that

could have been spirits, such as animals or plant substances, but that have

become things and that need to be restored to the immanence whence they come,

to the vague sphere of lost intimacy. (S, 213)

Remembering how he stresses that objects of sacrifice are

conventionally utilitarian objects and not luxury goods, Bataille’s account is

particularly illuminating when we turn back to Greuze. Emma Barker herself

argues that Greuze’s pictures of young girls apparently mourning a loss of

chastity and their implied paternal beholder (see below) need to be situated in relation to

the “social practice of the exchange of women, as it has been theorized first

by Claude Lévi-Strauss and subsequently by feminist scholars.” (RGG, 99) In the

deeply patriarchal society of ancien

régime France, Barker argues, “the deflowering of an unmarried girl was not

so much a sin against her chastity … as an offence against the authority of her

father.” (RGG, 99) Since women were regarded legally as objects to be

negotiated on a marriage market, sexual activity constituted a crime against

property, a violation of a utilitarian object.

Hence its drama. Per Bataille, the loss registered in the

weeping of Greuze’s young girls marks the sacrifice of their economic function

on a profane marriage market through a rupture of their commodity status, their

objecthood. Yet, this kind of operation is precisely what Fried seems to have

in mind with Diderot’s aesthetics and anti-theatrical painting writ large. The

new insistence on the beholder in France ca. 1750, he argues:

directs attention to the

problematic character not only of the painting-beholder relationship of

something more fundamental—the object-beholder

(one is almost tempted to say object-subject)

relationship which the painting-beholder relationship epitomizes. It suggests

that by the middle of the eighteenth century in France the object-beholder

relationship as such, the very condition of spectatordom, had emerged as

theatrical, a medium of dislocation and estrangement rather than of access to truth

and conviction. The essential task of the painter as construed by Diderot … was

to undo that state of affairs, to de-theatricalize

beholding and so make it once again a medium of absorption, sympathy and

self-transcendence. (TSF, 581)

Transcending the individuated self, the false opposition of

subjecthood and objecthood: surely these are goals reconcilable with Bataille’s

notion of sacrifice. But, they are also deeply continuous with the religious

fervor of “Art and Objecthood”—its opening appeal to the thought of

fire-and-brimstone Puritan minister Jonathan Edwards (author of the famous

sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”) and Fried’s revulsion at

minimalist work that “makes the

beholder a subject and the piece in question … an object” (A&O, 154), to

say nothing of the concluding line, “Presentness is grace.” (A&O, 168)

Indeed, one of the most productive observations made by Emma Barker in class

was that we should take this capacity of bourgeois society for the sacred

seriously since it helped to produce nothing less than the French Revolution.

By this account, then, what we see in Greuze’s supposedly

melodramatic, saccharine and otherwise embarrassing excursions into

sentimentalism are really mechanisms for restoring a sacred order through art,

which had been made necessary by the advent of new techniques of the self. I

think this is what Fried means when he concludes one of the preliminary essays

towards A&T this way: “If one

asks why beholding or spectatordom emerged as problematic and specifically

theatrical in France around the middle of the eighteenth century, one cannot

expect an answer in terms of painting alone. For what underlay that development

was at once a new conscious of the self and a new experience of the role of

beholding in the stabilizing (and undermining) of that consciousness. The

ultimate sources of the theatricalization of beholding must be sought in the

social, political, and economic reality of the age—in all that bears on the

history of the self.” (TSF, 583)[2]

This strikes me as one of the really productive sites for exploring Fried’s

vision of the moral in modernism in relation to the thought of Michel Foucault

and those who have built upon his work. But, I’ll save the elaboration on this

point for another time.

[1] This was not

entirely capricious on my part, as Caplan too references Bataille directly

before the passages quote above, albeit in a different context; FN, 21.

[2] This, of

course, is a fascinatingly different account from the dogmatism of A&T itself, where we read: “Nowhere

in the pages that follow is an effort made to connect the art and criticism

under discussion with the social, economic, and political reality of the age.”

(A&T, 4)

Abbreviations for works cited:

TSF Michael

Fried, “Toward a Supreme Fiction: Genre and Beholder in the Art Criticism of

Diderot and His Contemporaries,” New Literary History 6, 3 (1975):

543-585

AMTFP Michael Fried, “Absorption: a Master

Theme in Eighteenth-Century French Painting and Criticism,” Eighteenth-century

Studies 9, 2 (1975): 139-177

A&T Michael Fried, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of

Diderot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980)

HMW Michael

Fried, “How Modernism Works: A Response to T.J. Clark,” Critical Inquiry 9, 1 (Sept. 1982): 217-234

FN Jay Caplan, Framed Narratives: Diderot’s Genealogy of the Beholder (Minnesota,

1985)

S Georges

Bataille, “Sacrifice, the Festival and the Principles of the Sacred World,” in The Bataille Reader, eds. Fred Botting,

and Scott Wilson. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1997, 210-219

RGG Emma Barker, “Reading the Greuze Girl: The

Daughter’s Seduction,” Representations

117 (Winter 2012): 86-119

A&O Michael

Fried, “Art

and Objecthood” [1967], in Art and

Objecthood, 148-172

[1] This was not

entirely capricious on my part, as Caplan too references Bataille directly

before the passages quote above, albeit in a different context; FN, 21.

[2] This, of

course, is a fascinatingly different account from the dogmatism of A&T itself, where we read: “Nowhere

in the pages that follow is an effort made to connect the art and criticism

under discussion with the social, economic, and political reality of the age.”

(A&T, 4)

No comments:

Post a Comment