Roland Barthes's Camera Lucida acts as a nearly talismanic force in recent writing on photography. No less influential in cultural studies of the 1980s, Barthes early work on the photographic image—work produced under the influence of major

historical factors like the influence of structuralist linguistics, the force

of abstraction in art, and the coming of American-style consumer culture to

post-War Europe—has not stood up as well. That said, the writing of the early Barthes, like that of his contemporary André Bazin, betrays an interesting and enduring conception of the photographic image as importantly cloven, cleft in two.

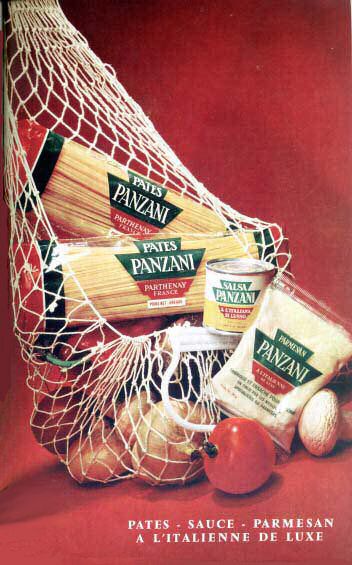

This point becomes readily apparent in Barthes’s “The Rhetoric of the Image” (1964), an essay that heralds a by-now-totally-second-nature reading of visual strategies of mass-media advertizing images such as this one at left. There, Barthes shows us, text and "connotative" cultural values struggle to apprehend and give order to the fundamental, "denotative" order of photography, which amounts a primitive ostention of the real. “From an aesthetic point of view,” he writes, “the denoted image can appear as a kind of Edenic state of the image; cleared utopianically of its connotations, the image would become radically objective, or, in the last analysis, innocent.” (277)

This point becomes readily apparent in Barthes’s “The Rhetoric of the Image” (1964), an essay that heralds a by-now-totally-second-nature reading of visual strategies of mass-media advertizing images such as this one at left. There, Barthes shows us, text and "connotative" cultural values struggle to apprehend and give order to the fundamental, "denotative" order of photography, which amounts a primitive ostention of the real. “From an aesthetic point of view,” he writes, “the denoted image can appear as a kind of Edenic state of the image; cleared utopianically of its connotations, the image would become radically objective, or, in the last analysis, innocent.” (277)

This utopian possibility of image freed from cultural codes

manifests uniquely in photography because of certain ontological

considerations:

This utopian character of denotation is considerably reinforced by the paradox already mentioned, that the photograph (in its literal state), by virtue of its absolutely analogical nature, seems to constitute a message without a code. Here, however, structural analysis must differentiate, for of all the kinds of image only the photograph is able to transmit the (literal) information without forming it by means of discontinuous signs and rules of transformation. The photograph, message without a code, must thus be opposed to the drawing which, even when denoted, is a coded message. [...] [end 277] In the photograph—at least at the level of the literal message—the relationship of signifieds to signifiers is not one of ‘transformation’ but of ‘recording’, and the absence of a code clearly reinforces the myth of photographic ‘naturalness’: the scene is there, captured mechanically, not humanly (the mechanical is here a guarantee of objectivity). Man’s intervention in the photograph (framing, distance, lighting, focus, speed) all effectively belong to the plane of connotation; it is as though in the beginning (even if utopian) there were a brute photograph (frontal and clear) on which man would then lay out, with the aid of various techniques, the signs drawn from a cultural code. Only the opposition of the cultural code and the natural non-code can, it seems, account for the specific character of the photograph ... (277-8)

So, where painting, drawing or any other hand-made

visualizing strategy can only ever move within always-already coded cultural

planes, the “causal” role of the depicted target in photography means that it

marks a confrontation between nature and culture, the pre-linguistic real and the

orders of coded language. (278) As Bazin will do in even more high-flown ways,

Barthes sees the photographic image as an epochal coupure—as necessarily and fundamentally other than those images

made by hand. Photography finds “humanity encountering for the first time in

its history messages without a code. Hence the photograph is not the last (improved)

term of the great family of images; it corresponds to a decisive mutation of

informational economies.” (279) And part of the point of this kind of semiotic

analysis is to show how and why that otherness is being co-opted, subjected to

the tedious banalities of commercial language to shift units in advertizing.

In his roughly contemporaneous “The Photographic Message”

(1961) Barthes gives a concise mission statement for cultural interpretation of

this kind: “The analysis of codes perhaps allows an easier and surer historical

definition of a society than the analysis of its signifieds ... We can perhaps

do better than to take stock directly of the ideological contents of our age;

by trying to reconstitute in its specific structure the code of connotation of

a mode of communication as important as the press photograph we may hope to

find, in their very subtlety, the forms our society uses to ensure its peace of

mind and to grasp thereby the magnitude, the detours, and the underlying

function of that activity.” (210) So, rather than asking what a society

believes, we ask instead how it implements or constructs those fantasies it

wants to believe. That seems like an interesting and productive enough idea.

But, in

what follows, it is hard to know if Barthes is attempting to diagnose the

ideological beliefs of post-War consumer society about photography or if he is

“telling it like it is”? What he claims certainly stretches credibility: “What

does the photograph transmit? By definition, the scene itself, the literal

reality. From the object to its image there is of course a reduction—in

proportion, perspective, color—but at no time is this reduction a transformation (in the mathematical

sense of the term.” (196) The photograph is a “perfect analogon” from what it depicts, a message without a code. (196) Just as he frequently presents statements like these in incredibly cagey ways—undercutting them with subclauses like "so it seems" or "as it were", subtleties that Krauss usually effaces—so Barthes complicates this position somewhat. He separates the

culturally-laded, connotative dimensions of photography (what will later be

called the “studium” in Camera Lucida)

from the denotative act (of the punctum). (197) Then, he likens the sight of

photography to interpreting an ideographic language, “which mix analogical and

specifying units, the difference being that the ideogram is experienced as a

sign whereas the photographic ‘copy’ is taken as the pure and simple denotation

of reality.” (207) Again, is he endorsing this view or is he just reporting? It's not entirely clear.

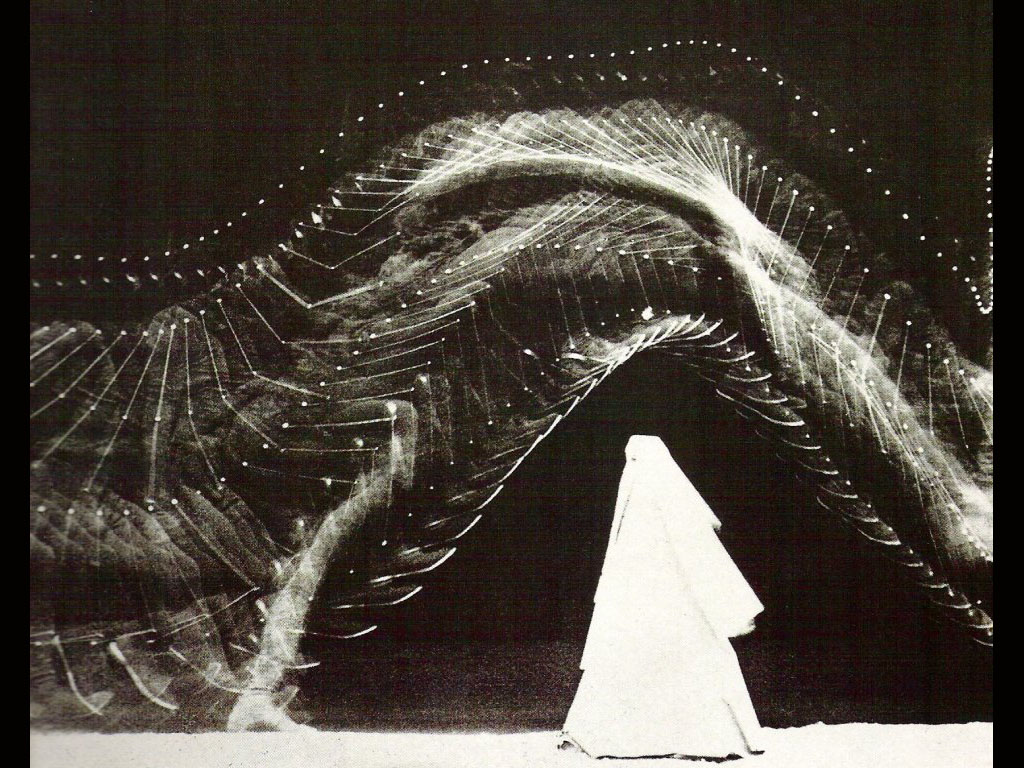

We get a very different story in “Camera and Mind” where

Josh Ellenbogen examines Marey’s photographs of targets invisible to the human

eye. Unlike the depictions of objects or people implicitly imagined in the

photographic practices discussed by Barthes and Bazin, Marey’s events have a

completely non-optical existence:

“If we put the matter into Peircean terms, we

can say the photographs are indexical relative to the events they picture, in

that a causal link exists [end 92] between them and their referents, but that

their status as icons has become problematic, at least as the idea of iconicity

is typically understood relative to photography. That is, to the extent that by

iconicity we mean a match with a sensory counterpart, such a match is not possible

for photographs of the sort Marey made, as they have no counterpart that they

can try to match.” (93)

Indexes without iconicity, these images don’t represent the

data that Marey wants to study; they are

his data. Thus, contra Barthes: “Marey’s practice centers on interposing a code

... between the observer and the event he or she studies, creating a visual

trace that makes the event register in a scientifically useful form. Minus this

interposition, this willful presentation of events in a language of glowing

lines and sinuous curves, Marey would have had nothing to examine.” (93) So,

far from being a message without a code, Marey’s images can only be a message

because they are encoded. While

Ellenbogen goes on to make a convincing case for how Duhem’s conception of the

idealization of objects into abstracted categories is necessary for scientific

thinking can serve as a useful framework for understanding how and why Marey’s

images were supposed to work, he makes some interesting comments on Duhem’s

conception of translation. (101)

No comments:

Post a Comment