These confusions abound in

chapters like “The Mast-Head.” Ishmael finds himself “a hundred feet above the

silent decks, striding along the deep.” (137) The ship and his body merge in a

fantasy of wondrous (literally, with reference to seven wonders of the ancient

world) monstrosity—“as if the masts were gigantic stilts, while beneath you and

your legs, as it were, swim the hugest monsters of the sea, even as ships once

sailed between the boots of the famous Colossus at old Rhodes.” (137) This

aggrandizing fusion of boat and body then expands still further as sea and self

become one: “Lulled into such an opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious

reverie is the absent-minded you by the blending cadence of waves with

thoughts, that at last he loses his identity; takes the mystic ocean at his

feet for the visible image of that deep, blue, bottomless soul, pervading

man-kind and nature; and every strange, half-seen, gliding, beautiful thing

that eludes him; every dimly-discovered, uprising fin some undiscernible form,

seems to him the embodiment of those elusive thoughts that only people the soul

by continually flitting through it.” (140) So, where Thomas

Willis had imagined the soul gazing out from its glass chamber into a

fountain-spume of heart-heated blood, Ishmael takes the liquidy world around

him as the insides of his brain.

Whatever we make of Bryan Wolf’s

"Emersonian" reading of this passage, a much more sinister self is discovered

later on in the sea of brit. “Like a savage tigress,” so Ishmael tells us, the

sea kills its own young; it has no mercy and no master. (247) He invokes:

“Consider the subtleness of the sea; how its most dreaded creatures glide under

water, unapparent for the most part, and treacherously hidden beneath the

loveliest tints of azure. Consider also the devilish brilliance and beauty of

many of its most remorseless tribes, as the dainty embellished shape of many

species of sharks. Consider, once more, the universal cannibalism of the sea;

all whose creatures prey upon each other, carrying on eternal war since the

world began. Consider all this; then turn to this green, gentle, and most

docile earth; consider them both, the sea and the land; and do you not find a

strange analogy to something in yourself? For as this appalling ocean surrounds

the verdant land, so in the soul of man there lies one insular Tahiti, full of

peace and joy, but encompassed by all the horrors of the half known life.”

(247) Now, there is one way of reading passages like these in which we might

cast Ishmael as an old salt who has the sea and whales on the brain and simply

sees the sailor’s life everywhere. This is the Ishmael who takes Nelson on his

column in Trafalgar square as churlishly impervious to a “hail from below,

however madly invoked.” (136) Or, the viewer who sees whales not only in

fossils found in “bony, ribby regions of the earth,” but also “in mountainous

countries where the traveller is continually girdled by amphitheatrical

heights; here and there from some lucky point of view you will catch passing

glimpses of the profiles of whales defined along the undulating ridges. But you

must be a thorough whaleman, to see these sights ...” (244) Like those

skrimshanders compulsively carving mazy, barbaric images of whales from whale

bones (243-4), we might say, Ishmael is obsessed with the totemic animal he follows (and is) to the point of delusion. He is just confused.

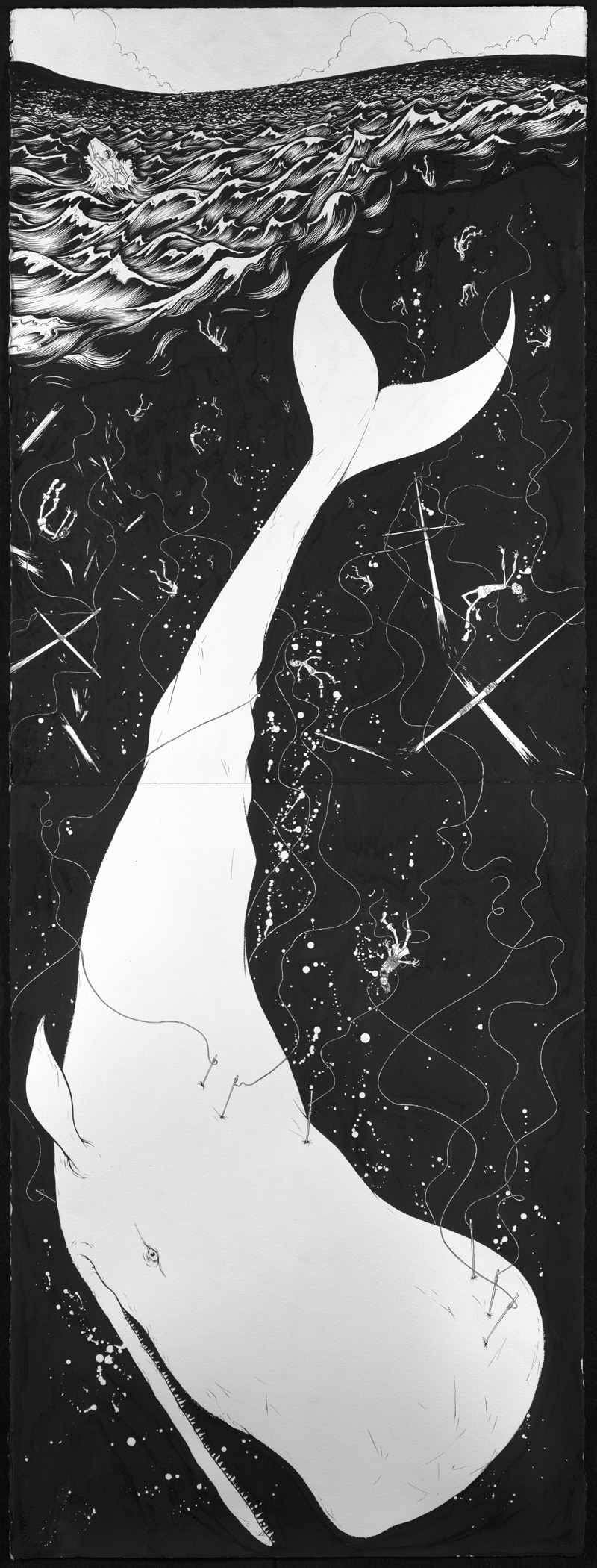

Yet, the confusions of self and sea, living

body and liquid, aren’t resolved by dismissing these as merely narcissistic

delusions. As we learn in “The Great Heidelburgh Tun” (named for a gargantuan,

eighteenth century wine vat depicted at left), the sperm whale’s head is both an impervious shield to the watery world outside it and a receptacle of the sea within. The head, Ishmael

tells us, is “of a boneless toughness, inestimable by any man who has not

handled it. The severest pointed harpoon, the sharpest lance darted by the

strongest human arm, impotently rebounds from it. It is as though the forehead

of the Sperm Whale were paved with horses’ hoofs.” (301) Yet, inside that thick

casing, which passes seamless through the water, is the "case" or

proverbial Heidelburgh Tun of the whale’s “highly prized spermaceti, in its

absolutely pure, limpid and odoriferous state. ... Though in life it remains

perfectly fluid, yet, upon exposure to the air, after death, it soon begins to

concrete; sending firth beautiful crystalline shoots, as when the first

delicate ice is just forming in water.” (303) Further, if the skin of the whale

is impermeable to liquid and yet bears liquid within it, the Pequod is also similarly constructed.

Given the fact that the sailors prefer drinking water from home, Ishmael

tells us, whaleboats move across the watery world carrying “a whole lake’s

contents bottled in her ample hold.” (340)

At a still further level, the mammalian

nature of the whale leads to all kinds of confusions. It breathes not by

receiving oxygen from the water like fish, but by surfacing, inhaling and

withdrawing “from the air a certain element, which being subsequently brought

into contact with the blood imparts to the blood its vivifying principle.”

(330) So, in water, the liquid-filled beast comes partially out of water,

inhales air, mixes air with watery blood, descends back into water, then

resurfaces and expels air in a plume of misty vapor as water meets air. (333-4)

Further, in the midst of “The Grand Armada,” Ishmael discovers a kind of

primordial, amniotic lake—perhaps like the ancient lake within and below Fingerbone

in Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping,

the pool of Dirce in Poussin's Birth of

Bacchus or the pool of Eden in

Milton—wherein the elementary nature of mammalian watery life are unfolding, the

young calves “leading two different lives at the same time.” (346) I'll return

to this pool in a moment.

The amphibious picture: I wonder

if this is what we might call the project of Gustave Courbet as read by Michael Fried?

What Fried calls attention to is the role of water in Courbet’s paintings, how

it is often used to trouble or undermine “the ontological impermeability of the

picture surface, by which I mean its standing as an imaginary boundary between

the world of the painting and that of the beholder.” (59) Fried enlarges upon the point by highlighting the role of water in Courbet's paintings in making their bottoms unusually boggy, soggy and squitchy. "There is a further point of resemblance," Fried tells us, "between the Wounded Man and the Sculptor [at left]: the way in which in the earlier painting the water in the immediate foreground functions as a natural metaphor of continuity, of the spilling-over of the contents of the painting into the world of the beholder, and therefore of the incapacity or the refusal of the painting to confine its representation (to confine itself) within hard-and-fast limits. If this seems fanciful, let me simply say that images of flowing water are deployed to much the same effect throughout Courbet's art ... and that in general the bottom edges of his paintings have a problematic status unlike anything to be found in the work of any painter before or since." (59)

If the fall of water makes the

soggy, boggy base of the picture

permeable, we might identify (at least) two other

kinds of water in Fried’s Courbet: the flows that carve out the picture-plane in serpentine paths (p. 120-125; 131-2) and the flood that offers a reciprocal, congruent model of the painter-beholder's own desire for union with painted world.

(209-215) But, why would these imaginations of water

be such an issue for Courbet? As I read it, Fried's claim is that Courbet’s art

followed on from a fundamental insistence on the painter’s own embodiment—one evolved (of course!) from the dynamics of absorption and theatricality Fried had previously charted through eighteenth century French painting, not to mention Minimalist sculpture. The crucial point here, though, is that these dynamics offer an explanation of why Courbet's self-portraits of the 1840s (including the Sculptor above) look so weird. Courbet, Fried proposes, is trying to

accommodate his conviction of his embodiment into the stock, specular models of

self-depiction availed by his culture. In many cases, he is failing spectacularly in that task.

Instead, what he produces are body-images that appear “disunified, multiscalar, technically disparate, and bizarrely orientated.” (73) Further, Courbet is compulsively and unconsciously imprinting the muscle memory and embodied traces of the postures by which his pictures are made into the representation. Thus, its less that he is showing himself to a beholder than constituting a self at the threshold of art: “In seeking to portray his own embodiedness—to revoke not only all distance but also, so far as might be possible, all difference between himself and the representations of himself—was in effect striving to annul, if not his own identity as beholder, at any rate something fundamental to that identity: his presence outside, in front of, the painting before him.” (79) Reckoning with Courbet, Fried argues, must require acknowledging the force of this position of "painter-beholder" which "the historical individual Courbet neither created nor controlled, that existed before him and in one form or another would survive his disappearance." (137)

Instead, what he produces are body-images that appear “disunified, multiscalar, technically disparate, and bizarrely orientated.” (73) Further, Courbet is compulsively and unconsciously imprinting the muscle memory and embodied traces of the postures by which his pictures are made into the representation. Thus, its less that he is showing himself to a beholder than constituting a self at the threshold of art: “In seeking to portray his own embodiedness—to revoke not only all distance but also, so far as might be possible, all difference between himself and the representations of himself—was in effect striving to annul, if not his own identity as beholder, at any rate something fundamental to that identity: his presence outside, in front of, the painting before him.” (79) Reckoning with Courbet, Fried argues, must require acknowledging the force of this position of "painter-beholder" which "the historical individual Courbet neither created nor controlled, that existed before him and in one form or another would survive his disappearance." (137)

While I won't try to reconstruct all of the complex, provocative hi-jinks Fried gets up to in elaborating the force of this "bottoming-out" of Courbet's paintings, his observations on the monumental Burial at Ornans (1849-50, now at the Musée d'Orsay) are highly suggestive in light of my confusions around Moby-Dick's cold fusions. Having called attention to the way in which Courbet affectively depicts his friend Max Buchon entering the funeral procession at far left, Fried writes:

While I won't try to reconstruct all of the complex, provocative hi-jinks Fried gets up to in elaborating the force of this "bottoming-out" of Courbet's paintings, his observations on the monumental Burial at Ornans (1849-50, now at the Musée d'Orsay) are highly suggestive in light of my confusions around Moby-Dick's cold fusions. Having called attention to the way in which Courbet affectively depicts his friend Max Buchon entering the funeral procession at far left, Fried writes:

"To think of the painter-beholder projecting himself quasi-corporeally into the representation of Buchon is thus to envision him joining the cortège at its source. And this suggests that the act of projection itself may be that source—that the painter-beholder's quasi-corporeal insertion of himself into the Burial via the figure of Buchon may be not only what impels the procession of mourners across the vast expanse of canvas to the right but also, in effect, what generates the procession: as if nothing less than all those life-sized, black-garbed, self-reiterating bodies or quasi-bodies could sufficiently absorb, could manage to contain, the heavy urgency of the painter-beholder's determination to achieve union with the painting before him and by so doing to annul every vestige of his spectatorship." (141)

Recall here the passage from Moby-Dick where, amidst the great armada of whales, Ishmael encounters that amniotic pool of mothers and babies: "The lake, as I have hinted, was to a considerable depth exceedingly transparent; and as human infants while sucking will calmly and fixedly gaze away from the breast, as if leading two different lives at the same time; and while yet drawing mortal nourishment, be still spiritually feasting upon some unearthly reminiscence;—even so did the young of these whale seem looking up towards us, but not at us, as if were were but a bit of Gulf-weed in their new-born sight." (346) So, like the cleft identity of the painter-beholder—and as with the two points of view to which Courbet's Burial answers (Fried, 136-139)—the young, water-born mammal leads a double life. Looking up through the liquid pane of the water in which it lives to the airy world in which it breathes from an impermeable body filled with liquid, the whale-calf gazes toward Ishmael while recalling a pre-lapsarian union with the maternal body from which it feeds. As with Courbet's refusal of proffered body-images, the whale looks at but does not cognize the humans above; it sees them instead as bits of floating weeds. On the picture-plane of the water as seen below, the humans become a macula—a blot like the black expanse of Courbet's mourners—blocking the whale's sight from its yearned-for fusion.